A Cutting Lesson September 10 2016

Sri Lanka is the mecca of the world’s finest natural gemstones. This island is blessed with the planet’s richest gem deposits as a result of an abundance of high-grade metamorphic rocks formed from the mineral belt that separated Rodinia, the super continent that preceded Pangaea. Throughout its rich history, Sri Lanka has gained a reputation from travelers from the far edges of the globe of its stunning collection of glittering gems. Marco Polo noted the abundance of sapphires, rubies and garnets during his exploration of the island in 1293, Pliny the Elder wrote of his encounters with fine gemstones from Taprobane, one of Sri Lanka’s former names, in 41 AD and the Mahavamsa (a chronicle detailing Sri Lanka’s earliest recorded history) describes the gem encrusted throne of a Naga King in 543 BC. Despite this blessing, Sri Lanka has not always been wise about the best use of these natural gemstones. One such blemish in its history relates to the process of gem cutting.

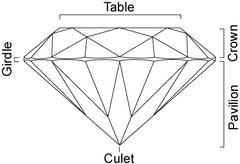

A cutter’s primary goal is to maximize the value of a gemstone given a rough. More often than not, this involves compromising in proportions to save weight and avoid any loss of money whilst retaining international standards for symmetry. However, with limited access to global markets, especially in the early 1900’s, and a host of government controls that restricted the sale of roughs, the best prices available for Sri Lankan origin gemstones were often capped. As a result, local dealers and cutters resorted to a native cut in which symmetry and proportions were marginalized and the orientation of the gemstone within the rough was prioritized. It was more profitable to export native cut parcels of gemstones, recut them abroad to the standards required by the international market, and resell them for a higher margin. So why are symmetry and proportions so important? Let’s find out! In the case of a gem where its pavilion is cut too shallow, there is a significant risk that it may develop a window that desaturates it color. In essence, the light entering through the crown of the stone, reaches the facet of the pavilion and is not reflected back in to the eye. And, because the pavilion is shallow, light from below travels through the pavilion and reaches the eye as well. As a result, the gem develops a ‘window’ in which its optimal color is less intense than if it had been cut to the correct proportions. In the case of a gem where its pavilion is cut too deep, there is a significant risk that an extinction develops where unattractive dark areas spoil the hue of the gem. Just like in a shallow cut pavilion, a deep cut pavilion does not reflect light back in to the eye once it reaches the pavilion facets. Instead, the light ‘leaks’ away from the gem due to the compromise in gem proportions. In either case, light leakages, either planned or not, have considerable impacts on the value of the gem.

So why are symmetry and proportions so important? Let’s find out! In the case of a gem where its pavilion is cut too shallow, there is a significant risk that it may develop a window that desaturates it color. In essence, the light entering through the crown of the stone, reaches the facet of the pavilion and is not reflected back in to the eye. And, because the pavilion is shallow, light from below travels through the pavilion and reaches the eye as well. As a result, the gem develops a ‘window’ in which its optimal color is less intense than if it had been cut to the correct proportions. In the case of a gem where its pavilion is cut too deep, there is a significant risk that an extinction develops where unattractive dark areas spoil the hue of the gem. Just like in a shallow cut pavilion, a deep cut pavilion does not reflect light back in to the eye once it reaches the pavilion facets. Instead, the light ‘leaks’ away from the gem due to the compromise in gem proportions. In either case, light leakages, either planned or not, have considerable impacts on the value of the gem. Several decades of this situation has meant that Sri Lanka lagged behind many markets in its development of technology and investment in precision cutting. It was simply more profitable to have the perfect cut after it leaves the sandy shores of paradise. However, as global trade became more integrated and international payments flourished, the possibilities of commanding higher premiums from within the borders of Sri Lanka improved. Instead of setting up branches abroad and incurring expensive cross border costs, local dealers began to invest in enhancing the local cutting process from the wealth of expertise they gathered from the international community.

Several decades of this situation has meant that Sri Lanka lagged behind many markets in its development of technology and investment in precision cutting. It was simply more profitable to have the perfect cut after it leaves the sandy shores of paradise. However, as global trade became more integrated and international payments flourished, the possibilities of commanding higher premiums from within the borders of Sri Lanka improved. Instead of setting up branches abroad and incurring expensive cross border costs, local dealers began to invest in enhancing the local cutting process from the wealth of expertise they gathered from the international community.

As a result, Sri Lanka has had the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of the pioneers in the cutting field and implement an industry that embraces best practices from across the world. Today, precision cutting standards in Sri Lanka are second to none and many gemstones that were sold in the bygone era of native cuts and are now reentering the global market are being recut to meet the new gold standard of symmetry.

Being blessed with natural resources does not grant the right of complacency. Sri Lanka has definitely learned that lesson. Perhaps, it serves as a lesson for all of us as well. Natural talents or attributes shouldn’t be taken for granted. Building upon them and continuously improving cements our position as leaders but the cracks won’t stop appearing. It is our responsibility to be aware of them and close them up as quickly and effectively as possible.